Who Set the Housing Trap?

Imagine a Vancouver where 80% of people can afford their own home. Residential streets are safe enough for children to play in. Most people live within walking distance of their work, their friends, their grocery store, and a lively nightlife. Streetcars trundle along, providing frequent, comfortable public transit. This sounds like an idyllic future, which could never possibly happen. It’s not. This is the Vancouver of the 1920s.

Now, let’s not romanticise the past. Women had only recently won the right to vote, and Asian Canadians were still being targeted by the racist head tax. More relevant to this discussion, the Great Vancouver Fire was within living memory, and the Boston Molasses Flood was hitting the headlines (yes, people genuinely were killed by the sticky syrup and yes, it really did put us on the path to unaffordable housing. We’ll get there). Still, though, there were many reasons why Vancouver in the ’20s was a stronger city than it is today. So who is responsible for the housing crisis we face today?

Before the 1930s there was very little regulation on where and how structures could be built, allowing nearly anyone with a dollar and two hands to build a shack on the edge of town. As their savings built up, they could slowly improve their home from a leaky shed, add a shingle roof, then one brick wall at a time, until it became a sturdy house. Vancouver was notable for having many apartments above retail stores, which allowed housing to also be a source of income. This enabled hard-working immigrants to start from very little, and build up enough savings to support their children moving into the center of town. When those children got there, they found many housing options at a variety of price points, including low-quality tenements, middle-class duplexes, high-end single-family homes, and world-class skyscrapers. This organic growth allowed Vancouver to grow explosively, from fewer than 30,000 in 1901 to 246,000 in 1931, while maintaining housing affordability, plentiful neighbourhood grocers and cafes, and a lively dance scene.

Google Maps and City of Vancouver Archives

This changed when Harland Bartholemew came along. Bartholemew was a pioneering urban planner, helping to found the American City Planning Institute in 1917. Born in Michigan, he learned his trade in New York before consulting for cities all over North America. In the early years of his career, three tragedies would shape his thinking, and therefore our cities.

The first tragedy was the rapid rise in car traffic. Where streets had previously been shared by trams, pedestrians, and horses in an informal manner known as ‘street ballet,’ Henry Ford’s new Model T was turning this dance into a bloodbath. Bartholomew saw this first-hand while conducting traffic counts during his training in New York, and would spend much of his career working to adapt cities to the new world of automobiles.

In 1919, the second tragedy occurred in Bartholomew’s home state. In January of that year, the Purity Distilling Company had been storing 2.3 million gallons of molasses when cold temperatures caused the vat to burst. This sent a tidal wave of dense fluid throughout the neighbourhood at 55 km/h, destroying houses and killing 21 people. Bartholemew blamed the death toll from the Boston Molasses Flood on the fact that the factory was located in a residential area. Just as he had been convinced that regulation and separation was the solution to traffic deaths, he turned to zoning to apply the same solution to housing.

The third tragedy which would shape Barthomew’s thinking was the ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic of 1918. Just as the COVID-19 pandemic stoked fear of crowded city centers and created a push toward suburban living, the pandemic of 1918 was blamed on the cramped living quarters of the poor in tenement buildings. This time Bartholomew landed on height and occupancy restrictions in his zoning to attempt to reduce density.

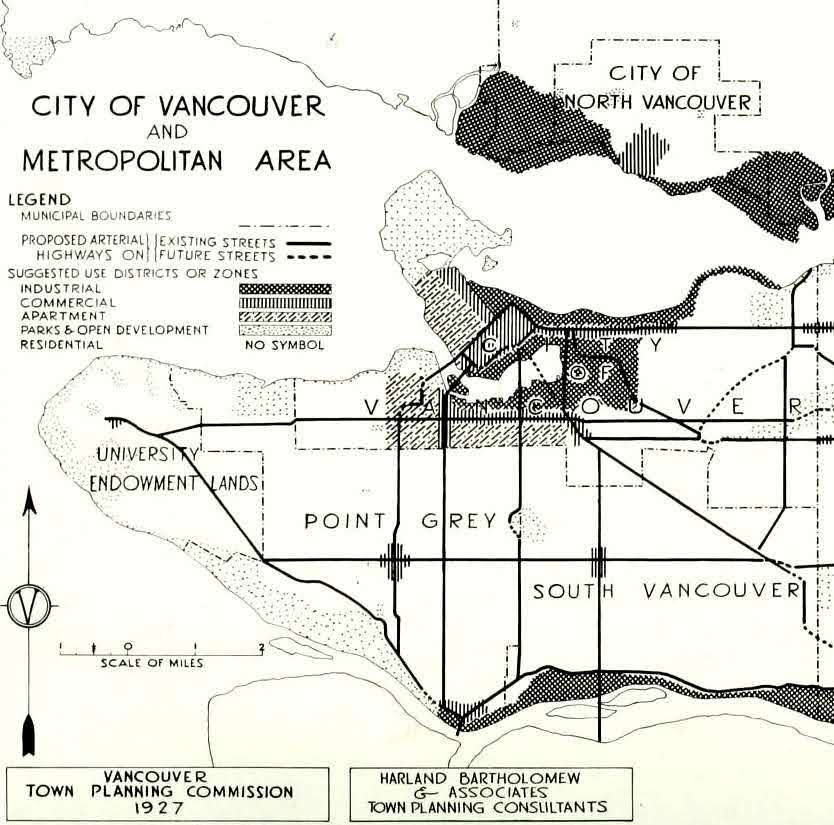

This was the context when, in 1928, Bartholemew was hired by the city to write A Plan for the City of Vancouver, British Columbia, including a General Plan of the Region. These plans were extensive, covering transportation, schools, parks, and some of Vancouver’s first regional zoning. He anticipated that Vancouver would reach 1 million people by 1960 and he attempted to create a plan which would accommodate all of them.

Unfortunately, between 1919 and 1928 his drive to improve public safety had taken a dark turn. Bartholemew worked to reduce vehicle deaths by moving pedestrians to the sidewalks and out of the way of cars. Automobile companies jumped at the chance to shift the blame from drivers to ‘jaywalking’ pedestrians, absolving themselves of the need to develop safety features until the 1970s. Meanwhile, his new zoning laws were quickly hijacked by wealthy, White landowners to create legal moats around their neighbourhoods. This allowed them to drive up property values by creating artificially scarce housing, and protecting them from having to share any of the rising land value with immigrants or the working class. While completing work in St. Louis, he wrote that his objective was to prevent migration into “finer residential districts… by colored people”.

This problematic ideology continued to develop in Vancouver. In the Plan, he stated “[t]he retention of Vancouver as a city of single family homes has always been close to the heart of those engaged in the preparation of this plan”. As a result, the Vancouver he laid out was suburban and exclusionary. Wealthy White residents prospered, while the working class, immigrants, and Indigenous people suffered.

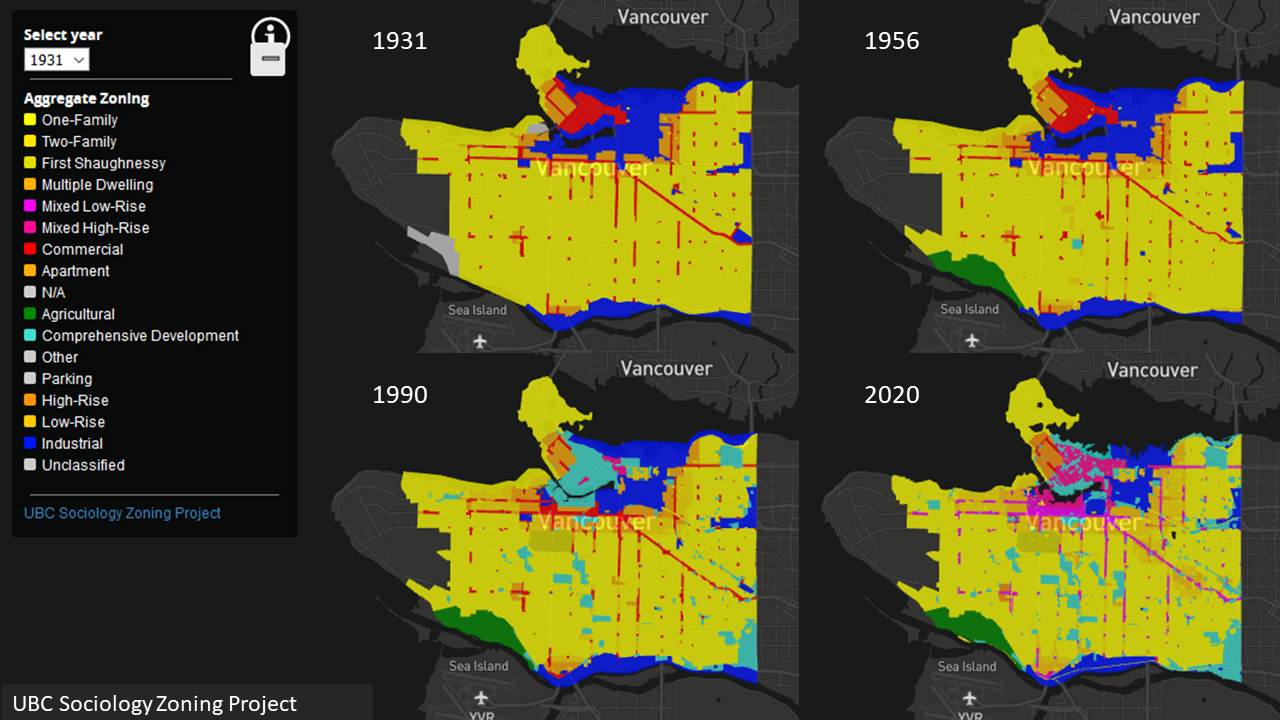

The Plan had another effect too. Before zoning, residents were able to improve a neighbourhood themselves. They could choose to create a house or an apartment, whether to rent or to own, and if they wanted to visit the neighbourhood grocer a few blocks away, or to drive to the commercial district. As the book Escaping the Housing Trap explains, people had a real stake in their community. Not only were they residents, but also as business owners with the ability to adapt to changing needs at a micro scale. Under zoning, this agency was taken away. The only opinions that mattered were those of city officials. By the 1960s, Vancouver’s population had diverged from the models created by Bartholomew, but they were still living in large part under the decisions he had made. Even today, Vancouver’s housing mix closely resembles the zoning laid out in 1928.

Imagine the immigrant family from earlier, now arriving in the 1950s. They are no longer able to build a small shack and improve it as they increase their income, since houses must be constructed to their zoning specifications from the start. The housing which is available to them is expensive, as new units must meet restrictions set decades ago and are not responsive to current demands. They can no longer earn their income by selling goods from the ground floor of their home, and must find additional money for a car if they want to commute to work or buy groceries. When their child is ready to move out, wealthy White homeowners will use zoning laws to prevent them from moving into the city. Bartholomew squashed the organic processes cities had used to meet the changing needs of their citizens for centuries, and condemned generations of future Vancouverites to live by his 1920s ideals.

The Plan failed almost immediately. If you know your history, you will have realized that it was published just a year before the Great Depression began. Wealthy Shaughnessy, which had already begun implementing zoning laws criminalizing rentals, became known as Poverty Hill. Homeowners found that they had just banned themselves from renting out any part of their house to cover for their financial losses, and many defaulted on their mortgage. Eventually, pressure grew and residents broke the new zoning law to convert their mansions into illegal rooming houses. After the depression ended, rather than learn any lessons from this experience, they returned to the Plan.

What lessons can we learn from Bartholomew? We know that the plan has continued to fail Vancouver, as housing prices have reached crisis levels and zoning has incapacitated developers from supplying enough to meet demand. We know that zoning laws are still used by the wealthy to protect housing prices and exclude working-class Canadians from neighbourhoods across the city, just as Bartholomew intended when he introduced the practice a century ago. Zoning is not everything, but the history of Vancouver teaches us that loosening the vice grip that zoning has on the city would go a long way towards letting the city adapt and respond to change again, and help us find our way out of the housing trap.